Amasya, Turkey

In search of Ferhad and Şirin - Turkey's most well-known love story

“You human beings,” the Iron Mountain tells Ferhad, “love one another in such strange ways… with your hearts, your spirits, your minds… …no wonder you are unhappy.”

But by this time Ferhad has already been labouring ten years to build the watercourse that will carry drinking water down to the cholera-stricken inhabitants of the city below. It is a tender moment in what is arguably the greatest of Turkish love stories: Nazım Hikmet’s play Ferhad ile Şirin.

As a young man, and not solely for his renown as an artisan, Ferhad catches the eye of the Sultana Mehmene. He is appointed as master craftsman to the palace and employed painting leaves and tulips; the decorative art known to the Ottomans as ‘nakış’. But before Ferhad can do a day’s work, the Sultana’s sister, Şirin, who has also swooned over Ferhad, summons him secretly to the harem and persuades him to elope. Of course, the two lovers are soon captured and returned to the palace to face certain execution, but out of sisterly love for Şirin and admiration for her young suitor’s eyes, Mehmene decides to spare them. Instead, she metes out to Ferhad the comparatively meagre task of forging a tunnel through the mountain to deliver spring water to the disease-ridden inhabitants of Arzen. Having paid his dues, his reward on completion will be Şirin.

But after ten years of labour, still driven on by his immense love, Ferhad is still only half way to finishing. Deserted by his erstwhile friends, his only companions now are the stars, mountains, trees and roe deer around him and the long years of solitude have grievously confabulated Şirin’s image in his mind. He admits to Venus (the ‘shepherd’ star in Anatolian folklore) that after such a long absence even her face eludes his recall. Tragically, his love has been crystallised by folding memory into this heroic act of folly.

Then, unannounced and under armed guard, Şirin arrives on the mountain. The two lovers are overjoyed to be reunited and furthermore Şirin brings the news that Mehmene Banu has revoked Ferhad’s punishment: the two of them should go and live in the kiosk in the palace gardens. Ferhad is shadowed by disappointment. He is too proud of his engineering feats to let his labours go wastefully unfinished and he suggests he build them a kiosk on the mountain; that they may live there while he completes his watercourse. Şirin will have none of it. There is a fine enough kiosk for them back at the palace.

“Very well then, will she come and visit him every day?” asks Ferhad.

But alas it is already too late. As Şirin turns to go, she tells her lover there was also a second edict from Mehmene Banu: unless Ferhad accepted to return to the palace immediately, the first condition would be annulled and he would not be allowed to set eyes on his lover until his labour was at last complete.

In search of the legend I travelled to Amasya, the reputed home of Ferhad and Şirin.

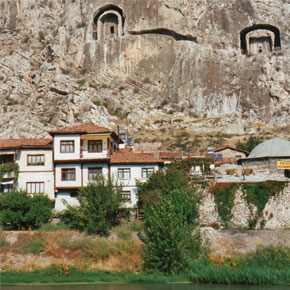

Set in a dramatic gorge on the Yeşilırmak river, Amasya is definitely one of the highlights of Northern Central Anatolia and with its mountaintop castle and Pontic rock tombs carved into the cliffs above and floodlit at night this is a spectacular setting. Even without the pretext of searching for old legends, the town is packed with interest. There is an abundance of attractive mosques, an ancient hamam and a fine archaeological and ethnographic museum, as well as a fascinating quarter of restored Ottoman houses on the shores of the Yeşilırmak river.

I stayed in one of these half-timbered mansions, once the home of a wealthy Armenian merchant. The pension had an air of opulence and luxury unusual to budget accommodation in Turkey and I was told that it was in one of these houses where the TRT filmed their version of Hikmet’s play.

Perched on the crags of the majestic Ferhat Dağı (which I imagine to be the so named ‘Iron Mountain’ in Hikmet’s play) is the sprawling citadel which dates, originally, back to Pontic times, though the surviving ruins are Ottoman. Into the mountain’s precipitous slopes are carved a succession of rock tombs; further testament to the Amasya’s Pontic origins, below which are huddled the ruins of the Kızlar Sarayı - evidently the palace harem. Scrambling around the tunnels that lead between the rock tombs fired my imagination. Could one of these be the secret staircase that led Ferhad to Şirin?

The lovers’ reputed grave apparently lies somewhere on the plateau beyond the citadel, though in the rain I skipped on the mountaineering to find it and stuck to pottering round the Ottoman houses below. Our choice proved provident, since on the ceiling of a room in the Emin Özkök Evi I came across the last surviving example in Amasya of Ottoman ‘nakış’, the art in which Ferhad was supposed to excel.

And if the tragedy of Ferhad’s folly hung heavy on my mind as I gazed up towards his mountain, the proof that Hikmet’s unwritten Act III, scene iii ended happily revealed itself around the mountain’s eastern skirt. Running parallel with the Amasya-Tokat road is the watercourse that inspired the legend; the Ferhat Su Kanalı, nearly six kilometres long. But concerning the origins of this magnificent feat of engineering, it is, of course, a matter of choice whether we believe Hikmet, or the archaeologists: who prosaically inform us it was built by the Romans.

First published in: ANATOLIAN ARCHAEOLOGY Research Reports of the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Volume 6 (2000).